“Why have the ruins of our own time been so devoid of value- historically, culturally and scientifically?” (Olsen 4). America is still relatively young, but grew rapidly during industrialization. We have established in Chapter 3 some of the reasons why the country, specifically the Midwest, has become so ruinous, with its ‘fast’, ‘awkward’ ruins. These structures hit all the marks of what it means to be a ruin- they are often only remnants, offering glimpses of history and of a very different society, but lack the antiquity that is mistakenly thought to be a necessity for value. We have a strange relationship with ruins; “a simultaneous concern for ruins but an absolute intolerance for ruination” (Olsen 15). This holds true in cities, where land is at a premium and development happens quickly and even more true in small towns, where there is very little development, insufficient funds and little attention is paid by the outside world as to what has value and what gets demolished.

Modern buildings with their modern materials are not given the same respect as historic brick or wood buildings by the general public and preservationists, and therefore the ruination or dissolution of such buildings do not garner the same romanticism. The perceived value of ruins seems to be directly related to age. As a society, we don’t value something that is in the process of ruining, just things which have already been ruined and transformed by nature throughout centuries. “[The ruin’s] sanctity is not a matter of beauty or of use or of age; it is venerated not as a work of art or as an antique, but as an echo from the remote past suddenly become present and actual” (Jackson 91). If age is the determining factor in the perceived value of a ruin, perhaps we should not be so hasty when deciding to demolish our modern ruins.

The American distaste for ruins, however, goes much beyond issues of aesthetics or materiality- it is related to politics, and can be traced back to the founding of the country, when “ruins functioned in post-revolutionary America more as emblems of political peril than objects of aesthetic pleasure” (Yablon 30). For young America, ruins represented ‘the fragility of Republics’ (Yablon 30), and the ‘over-civilization’ (Marx 140) which was occurring as a result of the Industrial Revolution in Europe.

“Given the rapid and seemingly relentless process of capitalist urbanization in the U.S., its ruins typically proved ephemeral” (Yablon 11), accounting for the shocking lack of ruins and history among suburban America. Similar to how Ralph Waldo Emerson described America in his 1833 poem “America, My Country” as a “land without history”, one can gather the same impression when traversing the country today- the vernacular, contextual, local ruin is often quickly replaced with something completely devoid of context- a national or multi-national chain or strip mall.

Post-Industrial Ruins

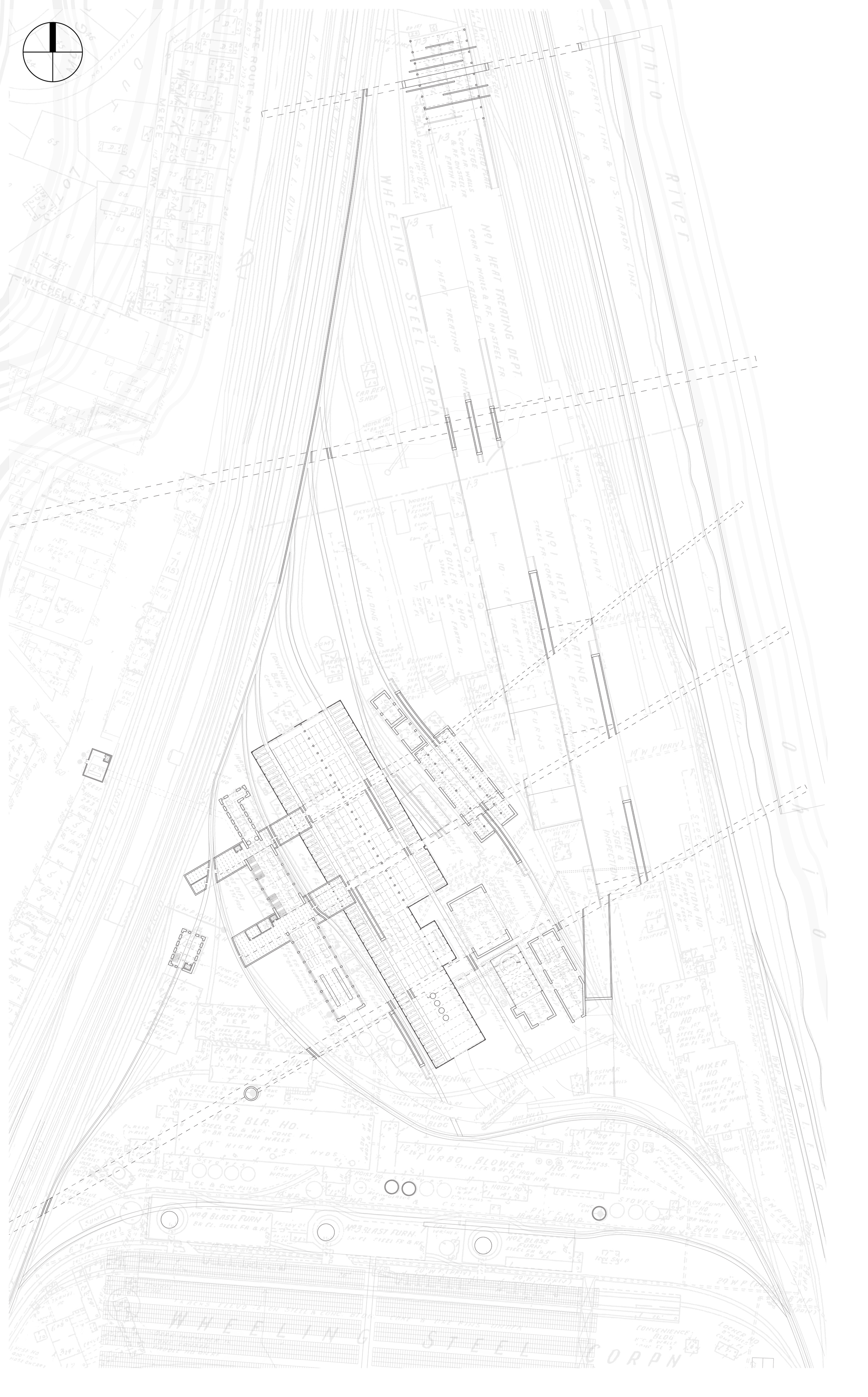

Machinery, even when actively adding to communities, can be alienating. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, people manufactured on a small scale for oneself and one’s family, seeing the entire process through. The manufacturer is now so far removed from the end product, both physically and mentally, so as to be almost completely withdrawn from the daily task itself. The machinery then turns one into a machine, until eventually the production floods the market and there is no longer a job. Thus these inherently alienating forms, upon abandonment, become even more alienating because they are seemingly useless, and their complexities only make sense to those who were involved in their processes. Even “on town maps, industrial areas are often represented as grey patches, indicating that from an urban point of view they are completely uninteresting” (Braae 43), and there are therefore no efforts to tie them into the surrounding communities, even prior to their becoming obsolete. Ruins, and particularly post-industrial ruins, never stood a chance.

Industrial buildings are essentially modern buildings, with their functional appearance and materials like steel, concrete and glass. In recent years, we have deemed it worthy to save those mid-century structures which are inhabitable, but other, auxiliary structures without quantifiable value are demolished, puncturing the post-industrial landscape. These sites have arguably more value than other historic building sites, for they display a timeline of transformation among multiple disciplines (manufacturing, technology, engineering, architecture) over, in some cases, the span of a century or longer.

Post-industrial ruins are endangered; we have seen the demise of most of our industrial heritage to vandalism, scrappers (spolia), and developers. This deconstruction is common throughout the history of ruins; the Roman Forum was leased as a quarry after the fall of the Roman Empire; trümmerfrauen, or rubble women, helped deconstruct and reconstruct post-World War II Germany; copper and bricks are stripped from abandoned historic buildings in cities throughout the modern world. The public is fearful of the dangers of brownfield sites, and often blame the sites themselves for high levels of criminal activity in their neighborhoods. “The industrial ruin is the contemporary equivalent of the picturesque view of a decaying Roman amphitheater” (Dillon), but as a country, we have yet to realize it.

German photographer Bernd Becher describes industrial landscapes as “entities that rise up from their surroundings like anonymous sculptures or anonymous structures that define their environment’s appearance and have become like a second form of nature: organs of technical existence.” In this sense, industrial sites are already like ruins, hanging in that precarious balance between appearing both natural and man-made. Post-industrial ruins are simply untimely ruins, succumbing to ruination during a time when society has the means and methods of demolishing extensive tracts of land swiftly, sometimes removing the memories of a place before there is time to debate alternate possibilities.

Ambiguity

Ambiguity is just one of the layers of the palimpsest of post-industrial landscapes. “Incompleteness and fragmentation possess a special evocative power” (Treib 3); we are initially attracted to ruins because of their incompleteness. Pieces have been deliberately removed and pieces have succumbed to nature’s relentlessness, leaving unintelligible gaps in the reading of post-industrial landscapes- landscapes which already require a certain amount of curiosity and thoughtfulness to understand due to their already fragmented assemblies. “We are learning to see [preservation] as a new (or recently discovered) interpretation of history. It sees history not as a continuity but as a dramatic discontinuity, a kind of cosmic drama” (Jackson 101). Where ambiguity in design may have been viewed differently in the past, it is simply unavoidable in ruinous landscapes.

“When we contemplate ruins, we contemplate our future. To statesmen, ruins predict the fall of empires, and to philosophers the futility of mortal man’s aspirations. To a poet, the decay of a monument represents the dissolution of the individual ego into the flow of time; to a painter or architect, the fragments of a stupendous antiquity call into question the purpose of their art” (Woodward 3). The ability for different interpretations provides an exciting and dynamic framework for designers in the preservation of post-industrial landscapes. An ambiguous landscape can be whatever visitors want it to be, as long as it is accessible and engaging.

Paradox

In ambiguity, there is often paradox, and in post-industrial ruins, there exists many paradoxes which add to the overall complexity and subjectivity. For example, ruination implies weathering, which can be seen as enriching and can be considered to add aesthetic value, but is also known to cause decay and dissolution. While representing memories, ruins are actively destroying memories through natural processes of destruction. The very idea of this ‘natural process of destruction’ of a ruin can be viewed from two angles; ruins are lifeless, and this fact is either emphasized through the process of ruination or can be viewed as a reanimation, something empty and static coming alive again with nature’s intrusion.

The contrast between the ‘wild’ and the ‘cultivated’- the machine and the garden, goes back to the beginning of the country and the challenge of reconciling the two opposing forces. One can see the inevitable triumph of nature over industry, or the relentless fight of industry over nature because the traces of industrialization never actually go away.

Ruins, by definition, must go through a process of abandonment and dereliction, “there has to be that interval of neglect, there has to be discontinuity; it is religiously and artistically essential. That is what I mean when I refer to the necessity for ruins; ruins provide the incentive for restoration, and for a return to origins” (Jackson 102). They represent something that has been clearly unwanted and abandoned yet retain some sort of value once that interval is complete.

In the Midwest, the paradox of post-industrial ruins lies most evidently in the collective desire to both remember and forget them, for it represents both prosperity and hardship for the region. The ambiguity of post-industrialism gives validity to both memory and anti-memory, however, by destroying signs of past success we may also be destroying potential for future success.

The memories found in ruins can be either personal or collective, as each person has their own individual memories of a post-industrial site, but there also exists memories that are shared by communities. The fact that ruins hold memories is a bit of a paradox because the term ‘ruin’ denotes decay and destruction. This paradox is especially visible in the Midwest where ruins are constantly being demolished- where memories are crystallized in the form of ruins, but ruins, especially in this context, are perhaps the anti-memory in their ability to efface a place of it’s history.

The ability of ruins to evoke challenging questions is part of their allure. Are ruins alive or dead? Do they represent presence or absence?

Memory

19th century English tailors called wrinkles and tears ‘memories’ because they “memorized the interaction, the mutual constitution, of people and things” (Olsen 10) (Stallybrass 196). This challenges the conventional definition of memories, no longer being strictly psychological, but having a physical and tangible presence, and blurring the lines between memory and history. When Aldo Rossi argues in The Architecture of the City that assembly of forms can be read as a summary of human history in a place, he is essentially talking about buildings reading as a timeline of collective memory.

Ambiguity allows us to create stories based somewhat on memory but relying on visual stimulus. It combines memory with imagination, often confusing the two and encouraging us to think about the relationship between them. It prompts memory in terms of the past, present and the future.

“Built structures, as well as mere remembered architectural images and metaphors, serve as significant memory devices in three different ways: first, they materialize and preserve the course of time and make it visible; second, they concretize remembrance by containing and projecting memories; and third, they stimulate and inspire us to reminisce and imagine” (Treib/Palaasma 2). Because these sites possess ‘layers of time’, which can be actively identified on a journey through the landscape, post-industrial ruins prompt us to remember something from our own lives or something from historical discourse, either about the site specifically or as a recollection of something related. This unique experience also prompts us to form memories in the present, as unique experiences, thoughtfulness, and the feeling of discovery often do. The fragmentation and incompleteness also has the power to encourage imagination, evoking images of the future of what the site could be or once was.

“Ruination can be seen as a mode of disclosure or revelation, and thus a form of recovering or bringing forth new or different memories” (Desilvey). A journey through a ruinous landscape can be a dynamic journey through uncovering the history of a place, with its discreet memories and ephemeral presence that changes with the seasons.

Identity

The ‘Rust Belt’ identity of the Midwest remains, but seems to be shifting back to more of a rural/agricultural identity. This shift skips over the most influential, transformative piece of the Midwest’s history. While the ‘Rust Belt’ moniker has negative connotations, it at least harkens back to the region’s industrial heritage and its influence on the urbanization of the country.

In order to not forget a large part of the Midwest’s culture and to retain an identity that is based on this culture, we must retain some physical pieces of it. In order to retain some physical pieces of it, we must recognize its value as it stands. As established in Chapter 4: Case Studies, one of the most difficult aspects of Haag’s design at Gas Works Park and Latz + Partners ongoing efforts to preserve post-industrial sites is convincing the public of the value of the site.

Post-industrial sites, with their alienating and desolate presence, can lack meaning for anyone who doesn’t have a direct relationship with them. In order for the public to give them value, the site must hold some sort of meaning on both an individual and a collective level. The precedent studies show that the designer can give meaning to the site, or rather make the meaning more apparent by exploiting the ambiguities and paradoxes as memory devices. Essentially, Ambiguity = Memory = Identity, where the vagueness of the landscape’s existing conditions, combined with design interventions, add to the idiosyncratic experience and begin to alter the identity of a place.

The weathering and ruination of post-industrial sites, working with the uniqueness of the sites themselves, have the ability contribute to place identity, adding meaning and significance for the community and ultimately contributing to community individuals’ conceptions of self.

To retain cultural and place identity, the region must be a palimpsest. Development can and must occur, things change and fall apart, but there must remain vestiges of the past in order to form a coherent present.